Thomas Ligotti’s Noctuary

Sometime in the mid-90’s I picked up an anthology or year’s best collection (I no longer remember which one) and read a Thomas Ligotti [Amazon|B&N|Powell’s] story. I would like to think that it was “The Last Feast of Harlequin” that forever changed my view of what cosmic horror could be, but in truth I just don’t remember. I do remember going looking for a collection by him, and being blown away by Songs of a Dead Dreamer. I couldn’t lay my hands on a copy of Grimscribe at the time, so a year-ish passed, and then I picked up Noctuary at the library. (Some wit had scrawled on the title page, in thick lead, “Ob-noxuary,” which wound up being another lesson, of sorts.)

Noctuary gave me what I later realized was my first exposure to anything that felt like what we now call “flash fiction” in the third part of the collection, “Notebook of the Night.” Among the stories there, “Autumnal” blended what I by then recognized as Ligotti’s signature worldview with all things autumn and a scrap of story-feel, and moved me in ways that very short fiction rarely had to that point.

Reading Thomas Ligotti led me to hunt down Bruno Schulz, and also, I’m a little embarrassed to admit, Franz Kafka. It wasn’t that I’d never read Kafka at all–I’d read several stories, in both English and German–but I hadn’t made a point of seeking him out in the context of cosmic horror or weird fiction generally. For that nudge, and for everything else, I’m grateful to Thomas Ligotti.

***

Low Red Moon, by Caitlin R. Kiernan

In 1998, I was roaming some bookstore or other and picked up a copy of Silk, the first novel published by then-newbie Caitlín R. Kiernan [Amazon|B&N|Powell’s]. I read the back cover copy, opened it to a page at random, saw a bunch of made-up words and something about angels, and I put that book right back on the shelf. It was the late ’90s, and horror was a shit-stew of late Splatterpunk, sketchy vampire novels, and wailing about the “end of horror.” The greats were failing to turn in great work, and trying-too-hard crap like Silk was flying under the “H” banner, so I figured horror could stand to compost for a while. A few years later, I saw that “that Silk person” had put out something “Lovecraftian” that involved… what? Dinosaurs? Time-traveling dinosaurs? Set in Alabama? “What the fuck ever,” I thought, and moved on. Surely this hodgepodge bullshit was not worth my time.

Never have I been so wrong about an author.

Fast forward to 2005. I’d been busy with grad school and had barely written a word of fiction from about 1998 to 2002 or so, and I’d been warming the writing engines up again during library school. I was wandering around in Magus Books in Seattle, and I came across a used copy of Threshold. It was $7.00, and I decided I’d give it a shot. Perhaps I might have been unwarrantedly dismissive. Reader, I have written at length in various places about the effect this had on me, but, in short, Caitlín R. Kiernan changed all over again my perception of what cosmic horror could be and do. I had been reading sundry Modernists for a while, and I’d developed the so-original idea of writing Lovecraftian fiction, but, like, with contemporary, taut prose, man. Reading Kiernan was exalting and devastating, because she did exactly what I wanted to do.

Not long after I read Low Red Moon, the sequel to Threshold, and it remains, to this day, one of my favorite novels of cosmic horror: delirious, beautiful, hinting at the shadowy world behind it all. I followed these up with a long-delayed read of Silk, which humbled me when I understood more about her aims, as well as Murder of Angels. About her short fiction it’s hard to say enough good things. If I one day manage to write a short story half as good as “Standing Water,” I’ll consider myself a real writer. When you can write an effective, striking story about a puddle, you have chops.

For her incantatory prose and leading me to think more broadly about the Lovecraftian tent, I’m grateful to Caitlín R. Kiernan.

***

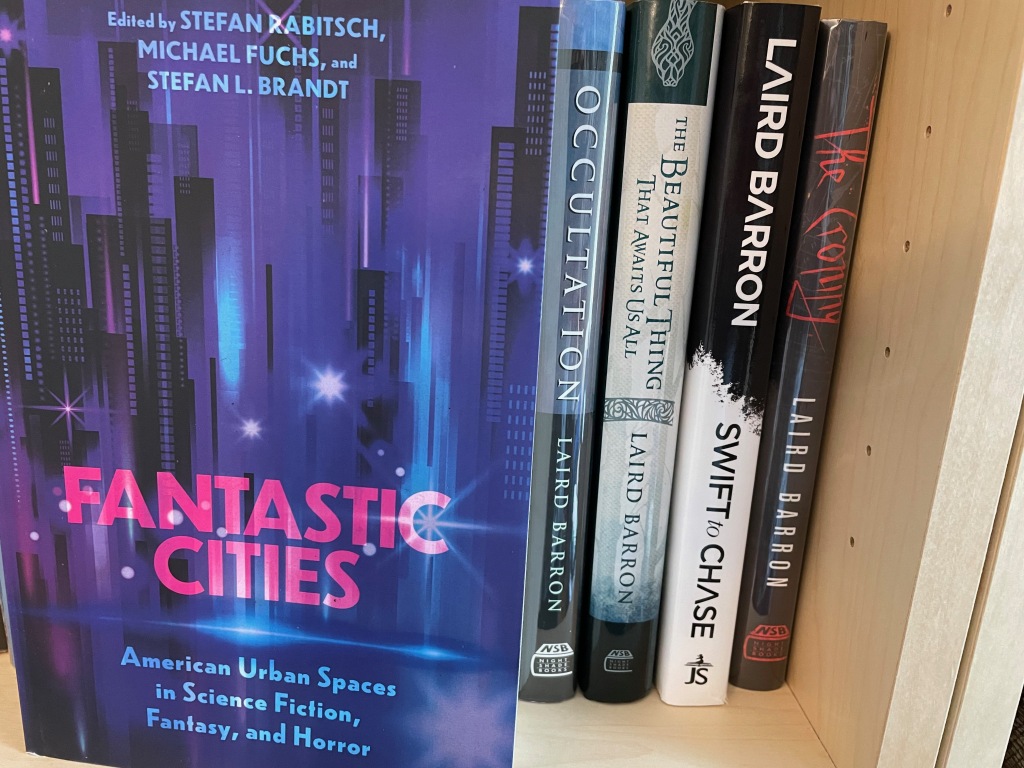

The Croning, by Laird Barron

At some point late in the Oughts I started to hear rumblings of a New Guy, who was the next cosmic horror sensation to watch out for: Laird Barron [Amazon|B&N|Powell’s]. This was years after I’d started up on LiveJournal, and I’d occasionally see this guy with Hemingway and other tough-guy userpics, and he seemed both smart and funny. I had come to grips with the idea that authors were, in fact, real people, but in the vicissitudes of LJ comments and conflagrations I hadn’t sought out any of his fiction. I was, after all, busy reading other things, and there was a whole world of other authors out there on LJ I wanted to read. Then, sometime in the spring of 2010, I picked up Occultation, his then-just-published short story collection, and, once more, I was off to the races.

You know where this is going, right? Laird Barron blew me away. The stories in Occultation were often long, which threw me for a loop at first. The 5-10,000 word story had never much appealed to me as a reader, and I still don’t do it much as a writer, but he made me consider the possibilities of the long story. En route, he mashed up Lovecraft, noir, and lengthy sentences, refusing to be rushed. I was impressed. I read interviews with him, followed his blog, and realized that here was another writer who cared about cosmic horror, not in the yes-I’ve-read-Lovecraft sense, but in a holistic, all-encompassing way that was more Weltanschauung than mere preference.

And then in 2012 came The Croning, his first widely-published novel. (His 2011 novel, The Light Is the Darkness, slipped under the radar and didn’t get very much attention.) The Croning is an unforgettable novel of cosmic horror. Hallucinogenic, vivid, and terrifying, it manages to pay homage to the forebears without feeling stale. Likewise, it’s unquestionably horror, and would alone have justified a revival of the genre, if it hadn’t already been cranking back up after the collapse of the ’90s. Why do I single out this novel for credit, which I read barely two years ago? There are many reasons, but the one I’ll cite is this: it’s a good short novel of cosmic horror. Short novels have always been around, but they aren’t much in favor right now, and if I need to think about what cosmic horror looks like at that length, I go to The Croning. That it didn’t win any awards is unfortunate, but there is a very long history of excellent works not winning awards for all manner of reasons. If I’m still around fifty years from now, and if I’m still rereading the books I have loved over the course of my life, I expect that The Croning will be on the shelf by my bed.

I’m grateful to Laird Barron for writing what he writes, as well as he does, at the length that he does. His engagement with and references to (in his fiction, interviews, and non-fiction) the masters of cosmic horror and the weird tale are a constant reminder that we are part of a tradition, and that strong trees have solid roots.

***

I’m grateful to these authors for the way their fiction has enriched my life and expanded my understanding of cosmic horror, and literature generally. I recommend their books to you, particularly those I’ve mentioned by name.